Part I: Growing, Harvesting and Preparing Horseradish

This project began with the horseradish. I’ve been growing it in my garden for several years at the base of my hazel tree and it is now well established enough to lift and split a root, ensuring a future crop, with enough to use as an ingredient.

This project began with the horseradish. I’ve been growing it in my garden for several years at the base of my hazel tree and it is now well established enough to lift and split a root, ensuring a future crop, with enough to use as an ingredient.

Horseradish does grow wild in the UK, including in urban spaces such as parks and cemeteries. However, it is difficult to forage for roots because you would need permission to dig them up, so it is a useful plant to grow in the herb garden.

This is the plant at full height in the summer (picture, left). According to the River Cottage Hedgerow Handbook, it is best harvested in early November, just as the leaves have died back. This provides a large root for using, and is good timing for making sure the plant recovers in the spring.

Here is what the root looks like after it has been split and washed.

Next, I peeled and grated it. Grating is not a pleasant experience as it releases the volatile compound allyl isothiocyanate, which is responsible for the pungency of the flavour but is also a vicious eye-irritant. Grating is best done outdoors or in a very well-ventilated space.

Part II: Making Mustard Balls

Looking for a period recipe to use my horseradish, I discovered “Tewkesbury mustard balls”.

In The Tudor Kitchen, Terry Breverton dates Tewkesbury mustard as “Fifteenth century to present”, mentioning that: “Legend has it that Tewkesbury Mustard Balls covered in gold leaf were presented to Henry VIII, when he visited Tewkesbury in Gloucestershire in 1535. The women of Tewkesbury gathered the ingredients from the field and the Severn riverbanks about the town.”

He says horseradish should be soaked in cider or cider vinegar and combined with mustard flour “then forming the mixture into balls which were then dried to aid preservation”.

Several companies sell Tewkesbury mustard or mustard balls, claiming to be using period information. One says: “Based on a traditional 15th century recipe… this is a perfect mustard/horseradish blend.”

I added a splosh of dry cider to the grated horseradish and left it to soak in. Later that day, I added mustard flour to the squishy horseradish/cider mix, adding a large spoonful at a time and stirring it in.

Theoretically, I would have done this until the mix was firm enough to be rolled into balls that held their shape, but I ran out of mustard flour, so the balls were slightly gloopier than ideal. This did not appear to affect the end result.

I put the balls into the oven on a very, very low heat. Checking on them frequently, it took around 8 hours for them to be mostly dry. After that I left them in an unlidded container in a dry environment to finish drying.

They become solid balls, from which flakes can be cut/scraped with a sharp knife.

Finally, some weeks later, I tried rehydrating with cider and tasting the mustard with some cold beef and salat

Yum – very pungent… and very portable!

Part III: But are they really Period?

There is certainly evidence that a product called “Tewkesbury Mustard” existed in period.

“Falstaff: He a good wit? Hang him baboon! His wit’s as thick as Tewkesbury mustard!”

Henry IV, part II. Date of writing approx. 1596-99 (first performed 1600)

There is evidence that dried portable mustard balls existed in period. Recipes suggesting spices and other ingredients to include in the mix exist from the 15th and 16th century, in more than one country. No pre-1600 recipe I’ve found includes horseradish. Here is Bartholomaeus Platina’s recipe from 1465, in De Honesta Voluptate Et Valetudine:

“Mustard Sauce in bits

“Mix mustard and well-pounded raisins, a little cinnamon and cloves, and make little balls or bits from this mixture. When they have dried on a board, carry them with you wherever you want. When there is a need, soak in verjuice or vinegar or must.”

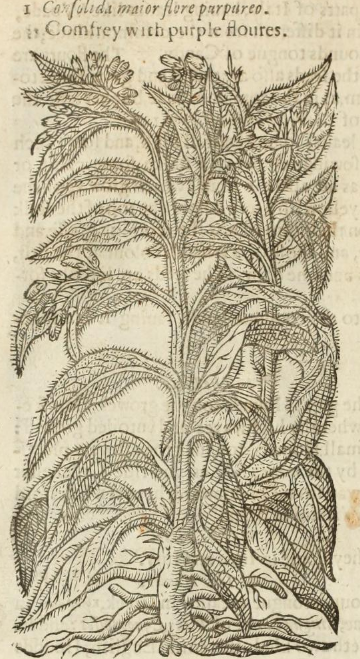

In John Gerard’s Herball of 1597, in the entry on horseradish, he mentions that the German people use horseradish sauce:

Horseradish stamped with a little vinegar put thereto is commonly used among the Germans for sauce to eat fish with, and such like meats, as we do mustarde; but this kind of sauce doth heat the stomach better, and causeth better digestion than mustard.

The History of the County of Gloucester notes that there is evidence from the Calendar of Patent Rolls (the administrative record of letters patent issued by the Crown):

“… a hint that mustard was made in the town in the 15th century comes from the record of financial links of inhabitants of Tewkesbury with grocers and spicers of London and elsewhere.”

And there is evidence of mustard balls made in Tewkesbury in 1639. Peter Mundy mentions them in his Travels:

The first off August 1639. I sett out from Glocester towards Worcester. Thatt night I lay att Tewkesbury. The mustard off this place (for want off other matter) is much spoken off. Made upp in balles as bigge as henns egges, att 3d and 4d each, although a Farthing worth off the ordinary sort will give better content in my opinion, this being in sight and tast much like the old dried thicke scurffe that sticks by the sides of a Mustard pott.” [spelling sic]

He does not mention horseradish. However, a Victorian editor of the Travels, folklorist and anthropologist Sir Richard Carnac Temple made an attempt to trace the history of Tewkesbury Mustard, with a lengthy “footnote” (attached here as an appendix).

There is evidence that Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn visited Tewkesbury for several days in 1535 during the progress of the royal court. The state papers and letters between Henry and his advisors contain scant evidence of where exactly they stayed, let alone what they ate.

I wrote to the company that claims to be following “a traditional 15th century recipe”. Here is their reply:

“Thanks for the enquiry!

“We have been making Tewkesbury Mustard for many years and have using this description for at least 10 years. It would be difficult for us to trace the source of the recipe due to personnel changes within the business.”

Ah.

IV Conclusion

I think it’s plausible that horseradish and mustard balls were made in Tewkesbury in period, but that it is nowhere near as certain as local town legend or the many modern sources citing that local town legend imply.

Bibliography

Wright, John. The River Cottage Hedgerow Handbook. Bloomsbury, 2010.

Breverton, Terry. Tudor Kitchen: What the Tudors Ate and Drank. Amberley Publishing, 2015.

Platina, Bartholomaeus, and Mary Ella Milham. On Right Pleasure and Good Health. Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1998.

Gerard, John, et al. The Herball Or Generall Historie of Plantes. Iohn Norton, 1597.

Mundy, Peter, and Richard Carnac Temple. The Travels of Peter Mundy, in Europe and Asia, 1608-1667. Kraus Repr, 1967.

Elrington, C. R. A History of the County of Gloucester. Published for the Institute of Historical Research by the Oxford University Press, 1968.

Henry VIII: July 1535, 1-10.” Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 8, January-July 1535. Ed. James Gairdner. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1885. 379-402. British History Online. Web. 25 May 2019. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/letters-papers-hen8/vol8/pp379-402.

Appendix – Richard Carnac Temple’s 19th Century Mustard Investigation. A “footnote” that runs for several pages.

* Tewkesbury mustard was famous in Shakespeare’s day and maintained its popularity until the 18th century when it was superseded by the so-called Durham mustard, said to have been introduced by a Mrs Clements of that City. In spite of such celebrity, no record has been discovered of any of its manufacturers nor of the site of their works, nor have I been able to ascertain the exact date of the discontinuance of the manufacture. In these circumstances, although entailing a long note, it seems advisable to print some of the information that I have succeeded in collecting on the subject.

To make the Tewkesbury mustard balls, the seed of the Brassica Nigra was pounded in a mortar, sifted, moistened with an infusion of horse- radish, and again pounded. The resultant mixture was so pungent that it gave rise to the proverb noted below.

The following are the most important references to the condiment, given in their chronological order:

1597: His wit is as thick as Tewkesbury mustard. Shakespeare, Henry IV, Pt. 2, II. 4.

1605: Tewkesbury… famous for… excellent mustard. Fynes Moryson, Itinerary f iv. 148.

1634: We did not will to goe out of our way to be bit by the Nose at Tewkesberry. Lansd, MS. 213, fol. 334. a,

1660: Tewkesbury hath a name for excellent mustard. Childrey, Britannia Baconica, p. 72.

1662: Gloucestershire,… Mustard…. The best in England (to take no larger compasse) is made at Tewkesberry…. Proverbs: “He looks as if he had liv’d on Tewkesbury Mustard.’ It is spoken partly of such who always have a sad, severe and tetrick [gloomy] countenance… partly of such as are snappish, captious and prone to take exceptions, where they are not given, such as will crispare nasum, in derision of what they slight or neglect. Fuller, Worthies of England (1662), ed. 1811, i. 374, 377.

1670: Proverb as above. Ray, Collection of… Proverbs, The proverb is found as late as 1855 in Bohn’s republication of Ray’s collection.

1679: The Deponent. . .met with Blundell and… asked him what he had, and he replied Tewkesbury Mustard balls, a notable biting Sawce, and would furnish Westminster when he had enough of them. Deponent saith that by Tewkesbury Mustard-balls we are to understand Fire-balls. Titus Oates, Narrative of the Horrid Plot and Conspiracy, &c., p. 48.

1699: Tewkesbury… is famous for its Mustard-Balls. Ogilby, Travellers’ Gtdde, p. III.

1712: Similar remark. Topog, Desc of Glocester shire, p. 12.

1720: Tewkesbury… the Town is famous for its excellent Chephalick [cephalic] Mustard Balls, which occasioned the Proverb for a Sharp fellow : “He looks as if he lived on Tewkesbury Mustard.” Owen, Britannia Depicta, p. 153.

1774: Tewkesbury…. It has been long noted for mustard-balls made here, and sent into other parts. Postlethwayt, Diet, of Trade and Commerce, i. s.v. Glocestershire.

1779: Tewkesbury…. The making of mustard-balls, as taken notice of in every book that treats of this place, has been so long discontinued as not to be within the remembrance of any person living. Rudder, Hist, of Gloucestershire, p. 738.

1787: Tewkesbury… famous for its mustard which is extremely hot and pungent, and therefore, by this property, supposed to communicate its qualities to persons fed with it. [Proverb, as above, quoted.] Grose, Provincial Glossary, s.v, Gloucestershire. See also 2nd ed. 1790.

1790: Tewkesbury was… remarkable for its mustard balls, which… occasioned this proverb &c. Dyde, Hist, of Tewkesbury, p. 63.

1830: Bennett, in his History of Tewkesbury says (p. 200 and note) that in his day the Tewkesbury mustard manufacture might have been easily revived since abundance of mustard, like that cultivated in Durham, was then growing wild.

1841: Tewkesbury has been long noted for its mustard, but it is at present chiefly distinguished for its manufacture of stockings. Pop, Encyc.y s.v. Tewkesbury.

1845: Tewkesbury. This town was once noted for its mustard. Encyc, Metropolitana.

By the “ordinary sort” Mundy probably meant used in the “ordinary” way at that period, that is, consumed whole not crushed and made into balls.

This project began with the horseradish. I’ve been growing it in my garden for several years at the base of my hazel tree and it is now well established enough to lift and split a root, ensuring a future crop, with enough to use as an ingredient.

This project began with the horseradish. I’ve been growing it in my garden for several years at the base of my hazel tree and it is now well established enough to lift and split a root, ensuring a future crop, with enough to use as an ingredient.

This was the project I entered at Michaelmas – my first A&S competition.

This was the project I entered at Michaelmas – my first A&S competition.